Inside an inconspicuous lobby in an office building on Walnut Street, there is a small express elevator with only one button to press: Floor 11. Hit the button, and 23.5 seconds later the doors open onto a mezzanine that should be grey offices, the drab trappings of corporate downtown life; but instead, you’re greeted with a beautiful tiled floor showered in warm light from a chandelier above, and Carlo Ponti’s gigantic Ruins of Rome photography. And then, to the right, impossibly and inexplicably, there it is: The Mercantile Library.

— 9 a.m. —

It’s 9 a.m., and the downtown member’s library feels like a library at, well, 9 a.m. Stillness. The sun warms the maple hardwood floors through the Mercantile’s soaring windows. The city hums faintly outside. The streetcar’s bell tolls as it sails along Main Street. The first thing one sees upon entering the library is an 8-foot-tall imposing yet graceful marble statue, acquired in 1856; a finger to her lips, she eponymously reminds us of the most traditional tenet of a library: “Silence.”

Mercantile Collector/Librarian Cedric Rose and I break that commandment. After we ascend a cast-iron spiral staircase to the library’s 12th-floor lecture room, I ask him what he thinks the public’s perception of the Merc is.

“I think that’s one of the main challenges of this place,” he says after a pause. “You have this archaic name — ‘Mercantile Library.’ We get a lot of people who are like, ‘Oh, are you guys a business library?’

“We have a few business books… from 1957,” he says with a laugh.

The Young Men’s Mercantile Library Association was founded on April 18, 1835 —almost 20 years before the Public Library of Cincinnati and Hamilton County. A group of 45 working-class merchants got together in a firehouse and decided to pool their funds so they could buy books and thus improve their knowledge, network and telegraph to the public that they were part of an esteemed organization that was reading instead of downstairs at a bar or brothel.

“Back in 1835 when this was a frontier city, people really understood that by educating yourself, you might be able to climb the social and economic ladders,” Rose says.

The library’s first incarnation in downtown’s Cincinnati College building was destroyed by a fire. The building’s owners didn’t have enough funds to rebuild — until the Mercantile’s members raised $10,000, which they pledged to the effort in exchange for a 10,000-year rent-free lease (with the option to renew, naturally), famously drawn up by Alphonso Taft, father to William Howard Taft. The second incarnation partially burned, and the Beaux-Arts building on the current site at 414 Walnut St. was eventually completed in 1904.

Today, only a handful of membership libraries still exist — and the Mercantile owes its nearly 200-year run in large part to that lease, Rose says.

In the lecture room, 22 names of legendary authors who have spoken at the library encircle the ceiling. Over the years the library has hosted Saul Bellow, Harriet Beecher Stowe, Ralph Waldo Emerson, Ray Bradbury, Tom Wolfe, Julia Child, Joyce Carol Oates, Salman Rushdie, John Updike, Elmore Leonard, even Herman Melville — whose talk in 1858 on “statuary in Rome” didn’t exactly garner rave reviews (newspapers at the time dubbed it “earnest, though not sufficiently animated for a Western audience”).

That’s the library’s past in a nutshell — a story so great that it’s easy to make it the only thing one talks about when discussing the Mercantile. But to do so robs you of the present, and perhaps even the library’s future.

Rose has been at the Merc for about 12 years, as has his colleague, Business and Membership Manager Chris Messick. And over those 12 years, Rose says, a lot has changed — notably the library’s perceived degree of Old Cincinnati exclusivity, which it has pivoted completely away from. Gone are the days when an unknown visitor would be regarded with suspicion, and perhaps even hostility. In fact, anyone can enter and read or look around for free. You only need an annual membership of $55 to check books out. (And there are more than 80,000 of them to choose from.)

Moreover, the library has grown into a full-blown literary center. In addition to the authors they bring in for lectures, they host myriad events, books and even have yoga on Saturday mornings.

Rose also bucks any notions of elitism. Noting that he comes from a background of working at coffee shops, he focuses on building personal connections with patrons. His day job has evolved from one of scanning old texts and sending them across the world to having conversations with members and getting to know their personal tastes, so that when they walk into the library, he can give them a tailored recommendation.

“For me, it’s customer service,” he says. “You want people to come here. You want them to find what they expect to find, you want them to have the excitement of finding what they don’t expect to find and, bottom line, you want people to use the collection and read the books. By any means necessary.”

— 11 a.m. —

By 11 a.m., more people have shown up. Some browse the long mahogany magazine stands, showcasing copies of Outside, Smithsonian, Wired, Vanity Fair, literary journals. Some sit around reading. A renowned micologist (one who studies fungi) works away at his laptop.

I ask Rose who his members are.

There are the classic library “power users” who check out five or six books a week. There are the freelance writers and students who quietly work from the library, never really interacting with the collection. There’s even a significant quotient of professionals from nearby businesses who come here to eat their lunch.

Near the circulation desk sits a hulking safe from the 1800s with hand-painted scenic views and florals. Rose begins to gather objects from it. He reveals one he recently unearthed simply by wandering the stacks — a history of Louis XII from 1615. The library’s treasures are manifold: True Prophecies or Prognostications of Michael Nostradamus, 1672. A George Washington autograph and signed letters from William Howard Taft. A first edition of Dombey and Sons by Charles Dickens. Rookwood vases and pots from the late 1800s.

And then there are the objects that more directly tell the story of the Mercantile: Rose produces a copy of the original 10,000-year lease and my eyes go wide. Behind the circulation desk is an oil painting of U.S. Senator Edward Everett by J.O. Eaton, completed shortly after he spoke at the library; Everett is perhaps best known as the person who opened for Abraham Lincoln and delivered a two-hour speech before the president delivered the Gettysburg Address in two minutes.

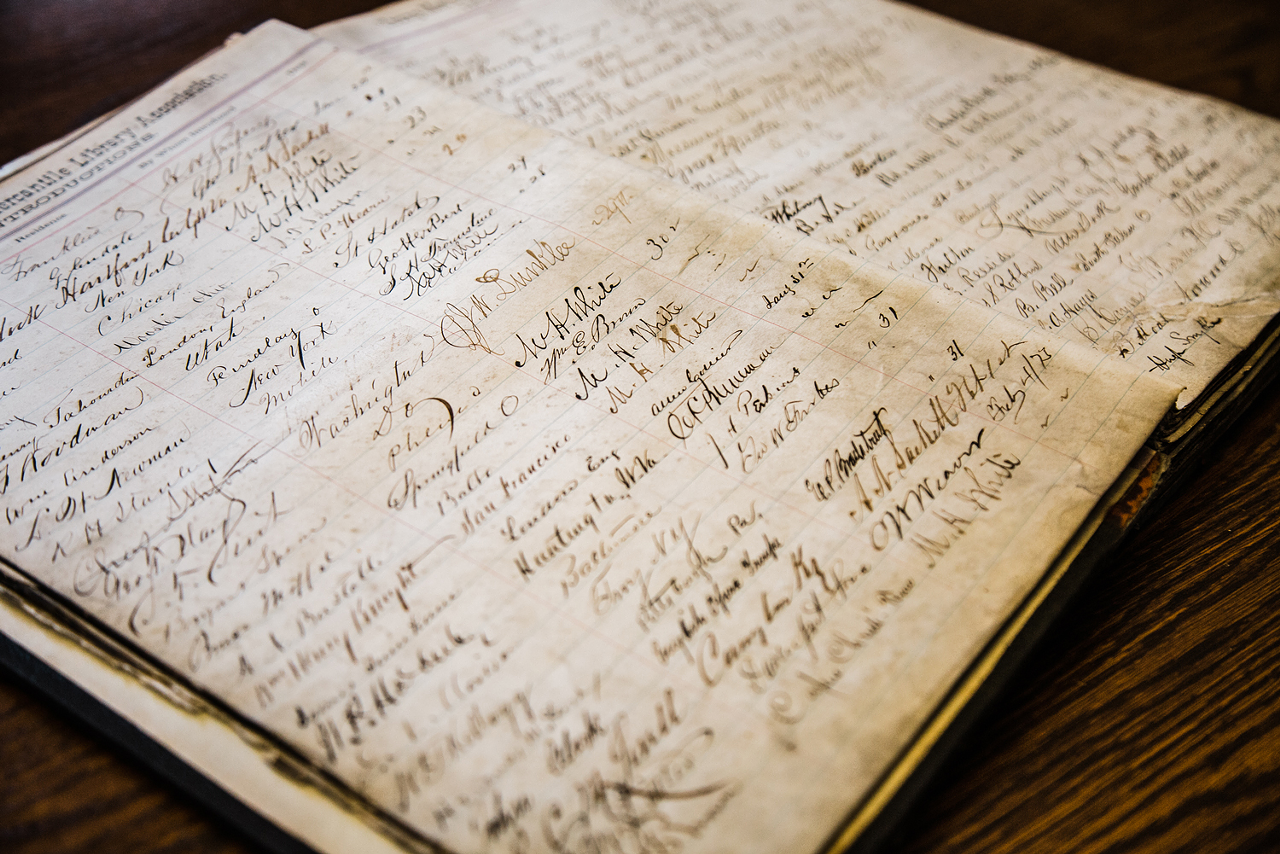

Rose carefully opens a bound set of the library’s original meeting minutes. One of his favorite highlights: After a round of drinks had been served (they tended to drink heavily at their convocations), the conversation turned to why the elevator operator was so cantankerous. He had a wooden leg, and they speculated it was perhaps because the leg had termites. This being the 1800s, every bit of such banter was recorded in beautiful, ornate script.

The handwriting, the lack of devices pinging and popping — “It was much more of a human world,” Rose marvels, his passion for the library, its collection and its future, alive in his eyes.

— Noon —

It’s noon, and I’m sitting at a long table with a man in a white collared shirt and striped tie, donning Apple earbuds and eating pretzels from a Styrofoam container. A microphone has been set up on a modest stage. Behind me, a man in a suit drinks a Coke Zero and picks at an array of bagged snacks as he plays on his phone. Two women work on laptops. Someone takes a bite of a turkey sandwich and a drop of mayo falls to the antique table. His eyes dart around to see if anyone has noticed. It seems an act of blasphemy. But as I’ll find out later, I’m missing the point.

— 1 p.m. —

“The fish don’t know if you’re a man or a woman,” Jen Ripple says as those in the room try to suppress a laugh.

It’s 1 p.m., and the library’s Messick is recording a podcast with Dun magazine Editor-in-Chief Ripple, and Tim Guilfoile, a board member at the Northern Kentucky Fly Fishers association. Messick, donning headphones, works the levels and monitors the conversation as it plays out in the lecture room.

It all feels surreal, and wildly out of place — fly fishers in a library. A library podcast episode focused on fly fishing. Hell, a library having a podcast, recording audio in what has historically been a temple of silence. But as Ripple and Guilfoile discuss the notion of women being stereotyped as out of place in the world of fly fishing, things come into focus.

The library started its 12thStory podcast a couple of years back. Episodes have focused on book discussion and interviews. Today, Ripple reveals she wanted to write about her love of fly fishing for a women’s magazine, but there really wasn’t one to write for. So she launched hers. Guilfoile and Ripple discuss the role of women in fly history, even the literature of fly fishing. As it turns out, Ripple notes, the first book on fly fishing (Treatyse of Fysshynge wyth an Angle), published in 1496, was written by a woman — a nun named Juliana Berners. All of this shouldn’t work, but it does.

As the podcast goes on, Rose quietly enters the lecture room through a side door and pushes on what looks like a wooden wall panel, accessing a secret door. Though it just houses the staff’s kitchen, it furthers the notion of the library as a place whose mysteries seem eternally manifold, a universe in the vein of Carlos Ruiz Zafón. What’s more, up here, the library floor seems lost, a foreign thing. Is this the soul of the Merc, versus its stacks of books? What is a library, if not those who populate it?

The recording finished, Guilfoile reflects on the Mercantile.

“I love it here,” he says. “It captures the essence of downtown Cincinnati. It’s not just a place — it has a personality.”

— 2:30 p.m. —

Tobacco Among the Karuk Indians of California by John P. Harrington, 1927.

What the Dogs Saw by Malcolm Gladwell, 2009.

The Best News Stories of 1923.

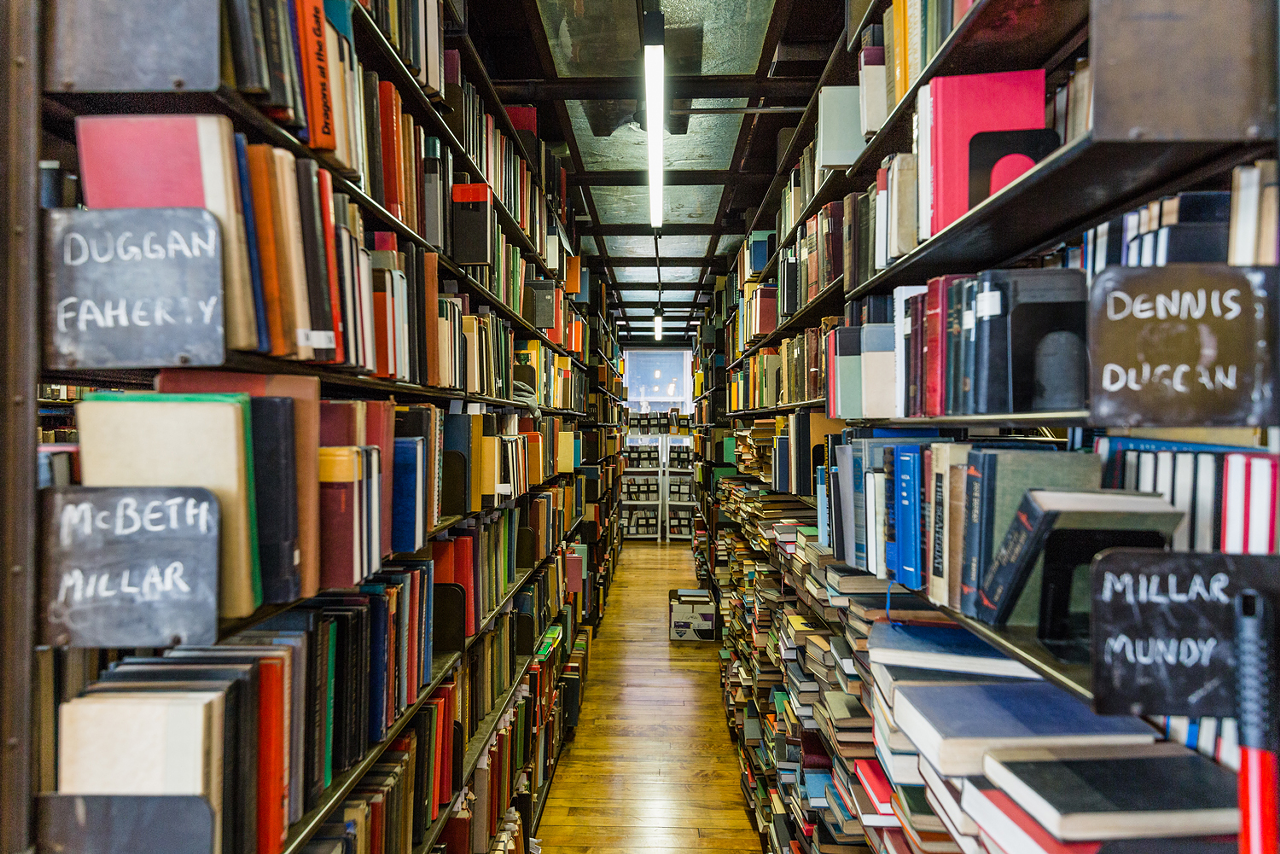

As a book person, wandering the steel stacks of the Mercantile Library, with categories and call numbers etched in chalk on the sides of each row, is akin to a spiritual experience. An experience, I might add, most newcomers don’t think is possible until they see someone else wander in. Up the staircase and into the stacks — with their amazing glass floors, so designed to allow for light to filter through them — the smell of books is intoxicating.

The Power Formula for LinkedIn Success by Wayne Breitbarth, 2011.

Satan: A Libretto by Christopher Cranch, 1874.

The Varieties of Dogs, as They are Found in Old Sculptures, Pictures, Engravings and Books: With the Names of the Artists by Whom They are Represented, Showing How Long Many of the Numerous Breeds Now Existing Have Been Known by Ph. Charles Berjeau, 1863.

Moreover, it’s easy to forget that you can check any of these books out. Up until last week, you could have theoretically checked out the Louis XII book from 1615, though something tells me Rose might have intercepted it.

As I’m browsing, I bump a well-worn wooden step ladder and cringe in horror as it echoes throughout the library. As I discover again later, though, to do so is to miss the point.

A woman arrives and two young girls accompanying her go flying up the stairs to the stacks, marveling at the city views and the novelty of the glass floor. She browses the new books displayed in front of the circulation desk — the latest from thriller writer Lee Child, Michio Kaku’s The Future of Humanity, David Neiwert’s Alt-America.

The lunch crowd had dissipated and people talk in hushed voices. “Silence” looms large, and is respected. But as tonight will show, to blindly obey her is to also miss the point. She’s a relic from the past — a beautiful, crucially important relic, but just that.

— 3:30 p.m. —

Rose and his colleagues get to work moving historic, priceless furniture with daunting speed and precision: The magazine racks are rolled away. Antiques are repositioned. Stacks of plastic chairs emerge from a closet.

Literary Programs and Marketing Manager Amy B. Hunter and I look on. Events like tonight’s talk with novelist and Mountain Goats frontman John Darnielle call for all hands on deck for their nimble staff of five.

“They pretty much have it down to a science,” she says. “It’s a beautiful game of Tetris.”

While people sometimes liken the library to something out of Harry Potter’s Hogwarts, Hunter likens it to Hogwarts’ Room of Requirement, in that “we’re whatever you need or want.”

She takes stock of the library. “This place will outlast us all,” she says after a moment.

Executive Director John Faherty sees the two little girls and asks if they want some cake. Faherty, of bombastic, energetic, good-natured personality, disappears into the kitchen for a moment and reemerges with a chocolate cheesecake, brought by a volunteer who regularly ferries such delights to the library.

The area is quickly readied for the night’s lecture, set to draw nearly 200 people — save the distribution of the chairs, which Faherty assigns to his teenage son, Theo, who’s undergoing some light punishment at the moment.

“Child labor laws,” Faherty jokes, turning to the staff — “If you see him slacking, ride his ass!”

I follow Faherty to his office, where he takes a seat as a bust of Chairman Mao peers at me over his shoulder. The first time Faherty came to the Merc in 2014, he was a reporter for The Cincinnati Enquirer.

“My initial reaction was probably the same as everyone else’s,” he says. “It was like, holy cow. And then my next thought was, How did I not know about this place?”

To justify taking some photos, he decided to write a story — subsequently headlined, “Is Mercantile Library the City’s Prettiest Place?” And in the story are the seeds that would come to define his tenure as the library’s leader a year or so later: It’s a working library. And everyone should be able to enjoy it.

“I would say we have to stop being a well-kept secret,” he says. “We have to become a poorly kept secret. Or not a secret at all. … I hate secrets. Maybe that’s because I used to be a reporter. When you really think about a secret, a secret only has value if you’re keeping it from someone. And who the hell are you keeping this place a secret from?”

Even writing this story, it’s easy to feel a bit like a traitor — you selfishly want to keep it to yourself. But again, that’s to miss the point, and perhaps why Faherty was hired after outgoing director Albert Pyle retired. I muse with Faherty about how I stood around outside earlier to see if anyone would stop and read the “Historic Cincinnati” sign about the library. He lights up.

“I hate that thing because it looks like a historical marker. It looks like a Civil War battle! If it disappears one night, don’t call the police,” he says with a laugh. “It looks like a historic marker and we are alive. One of the things I try to tell people is we are a library — we are not a museum.”

Faherty says the library currently has more members than it’s had in 100 years: 2,800. As the book Literary Cincinnati notes, the library peaked at 4,000 members in the 19th century, but had dropped below 300 in 1968 before making up some ground and hitting 1,000 members in 2000. However, the better metric for success, Faherty says, is that they’re more utilized today than ever. In 2015, the library had 4,200 people come to events. Last year they had 7,000.

Still, that’s not enough for Faherty. In discussing an unpopular opinion that we share about Moby-Dick (a heresy that cannot be included in any article about a library), I ask him what his white whale is. He pauses for a series of moments. “My white whale is keeping this place fantastic. Not changing the place — but changing who uses it.”

Diversity. Faherty’s goal is to have the library become more diverse, younger and more active. “We need to better reflect our community. We don’t. We’re working on it. We’re working on it literally every day,” he says.

It’s a fact, he says, that the Merc could shut its doors and admit no new members and still be a fully functioning, fully staffed, active library.

“We could do that for thousands of years. And while it’s a great short story, it’s also such a creepy thing,” he says. “I mean, I really believe this place is kind of magic. And more people should know it. If we’re an active library, we’re a successful library. We live in weird times. It’s 2018 and the world feels a little bit nuts and no one believes anybody. And disagree means fight. This is a place where people believe stuff.”

As for how the library operates, given his hatred of secrets, he readily hops onto his computer to pull financials.

This year, Faherty says The Mercantile Library’s budget is $1 million — the largest it’s ever been. Membership dues net about $126,000. The rest is a mosaic of member contributions, event sponsorships and the library’s investment fund. And, of course, there’s the organization’s signature annual fundraiser, The Niehoff Lecture. Combined with other events, it brings in about $110,000. This year, the library scored a massive coup by booking Margaret Atwood for the lecture, which takes place on Nov. 3. The rest of the 2018 lineup is equally impressive — in order of appearance, Steve Earle (who performed March 14), Susan Orlean, Melissa Clark, Colson Whitehead — and yet it comes with problems of its own.

“This is a shocking group of writers,” he says, eyes wide. “This lineup is insane. This lineup makes me so nervous. There’s no way I can top this lineup.”

His son, Theo, returns.

Faherty tells him to ask Rose for a good book. “He’ll ask you a couple questions, and then I want to know what he comes up with. Hey, Ced!”

“Yesss?”

“Would you help Theo for a minute? This is library work.”

And the library goes on.

“Us doing our job is asking one of our favorite questions of all time,” Faherty says. “Which is: What are you reading? There is no better job in the world than that. Where that question is central to what I do for a living, is to know what you’re reading.”

“So,” he says, a devilish look in his eyes. “What are you reading?”

— 6 p.m. —

It’s the calm before the storm. Literary Programs and Marketing Manager Hunter’s husband arrives and helps set up the bar. Around 6 p.m., the die-hard John Darnielle fans start to trickle in ahead of the 7 p.m. program. People who seem new to the library mill about, looking delighted, and perhaps a bit unsure. They eye the bar — can you really drink here? They take selfies with the stacks in the background — do you think can you go up there? A man wanders up as I work in a corner — can he ascend the stairs to the overlook area?

The light outside begins to dim. Newcomers approach Messick, who is manning the guest list, to ask what the library … is. He explains.

The room fills almost completely. The staff estimates it’s 50/50 members and nonmembers. It’s a hip, eclectic crowd. Messick takes a moment away from the table to introduce Darnielle. (And he does so with humor and grace, though he’s been working for almost 12 hours.)

It’s dark outside now. The giant circular bulbs that punctuate the library’s ceiling reflect in the windows.

Darnielle is funny. Sharp. He reveals he has a Tolstoy cookbook. He talks about the new paperback release of his novel Universal Harvester, and reads a chapter from it. He tells stories about working the A/V desk at a library.

The Q&A ends and a line of bubbling eventgoers forms to get their books signed. They’re delighted. It’s loud. Darnielle signs, “Silence” regarding him a few feet away.

I look around, and realize the extent to which I had the library wrong. A library is not meant to be kept for oneself. Yes, it is a repository of books and reflection. But it’s alive, as it has been for the past 183 years. Perhaps more bluntly put: The mayo belongs on the table.

A couple hundred plastic chairs sit next to historic cast-iron hat racks, magazine racks and an old Geneva Regulator clock acquired by the library in 1852. A bronze bust of Robert Frost has a Cincinnati Reds cap perched atop its head.

Perhaps Rose framed it all best earlier.

“I came in this morning, and noticed that the weight on our Regulator clock was almost at the bottom. So I’m opening a safe with a dial lock, I’m cranking up the counterweights on this clock but then …”

He pauses.

“It’s just really weird because this place is like an anachronism but also living in the present.”

The clock embodies time. But it behaves in a different way here.

To cite Slaughterhouse Five by Kurt Vonnegut — a writer who shockingly never spoke at the library though he seems tailor-made for it:

“All moments, past, present and future, always have existed, always will exist. …It is just an illusion we have here on Earth that one moment follows another one, like beads on a string, and that once a moment is gone, it is gone forever.

… So it goes.”

The Mercantile Library is located at 414 Walnut St., Downtown. More info: new.mercantilelibrary.com.