The surrounding neighborhood is rapidly becoming whiter and wealthier, but the West Oakland BART station still feels like it’s in a somewhat poor and solidly black neighborhood. Black vendors outside sell jewelry, incense and shea butter. A few revolutionary communists mill about in fanny packs and graying ponytails, hoping to convince the commuting lumpen to take a newspaper. Opposite the station, across 7th Street, a mini-strip mall is home to a check-cashing spot, a no-frills eatery called Donuts & Burgers, and a convenience store.

West Oakland isn’t an outlying neighborhood or inner-ring suburb. It’s in the heart of the Bay Area, the last stop on the east side of the bay before BART riders tunnel west and emerge minutes later in San Francisco’s Financial District. Four of the system’s five train lines pass through this station, and its large parking lot accommodates drivers who’d rather get on board than deal with the Bay Bridge’s long waits or tolls. Because it’s central, 14 black activists affiliated with Black Lives Matter organizing knew that if they could stop a train in West Oakland on the November shopping holiday known as Black Friday, they could bring BART—the nation’s fifth busiest rapid transit system—to its knees. They did, for several hours. There’s been hell to pay ever since.

Members of the group, now known as the Black Friday 14, are each charged with violating a California law that prohibits interfering with train operation, a misdemeanor. Until mid-February, they have also been on the hook for $70,000, an amount BART said the protestors owed the institution for lost business. By rallying hundreds of vocal supporters to show up at BART board meetings and court dates since the start of the year, the activists have turned their legal ordeal into an opportunity to keep talking about the issues they wanted to raise in the first place— the transit system’s role in perpetuating violence against black Bay Area residents.

Black Lives Matter protests dominated headlines in the final months of 2014 following grand juries’ failure to indict police officers Darren Wilson and Daniel Pantaleo for killing two unarmed black men, Michael Brown in Ferguson and Eric Garner in Staten Island. For a minute there, it seemed like America was ready to talk about race and police brutality. But since then, much of the sympathetic coverage of the movement has died down. The December killing of two NYPD officers by a mentally unstable gunman and the subsequent standoff between the police union and the de Blasio administration eclipsed the focus on the organizing, as have statements from high-profile black people, including Oprah Winfrey and Al Sharpton, that raise questions about whether Black Lives Matter organizers actually have a game plan that can lead to lasting change. The central conversation that started last year continues to get lost, buried by distractions. Just yesterday, some observers attempted to blame the movement for the non-fatal shootings of two officers in Ferguson.

What’s been missed as journalists’ attention has shifted either to cynicism about the movement or elsewhere entirely is that the fight for black lives is continuing on the local level, as it had before Mike Brown and Eric Garner became household names. Nowhere is this clearer than in the Bay Area, where a spirit of righteous defiance—of refusal to go along with the official narrative—motivated the Black Friday 14 to shut down BART, an institution that’s long been considered at odds with black Bay Area residents. That act of civil disobedience made it possible to feel some control, some agency at a time when the legal system was telling black people again and again that they had little of either. “People felt empowered,” 23-year-old Devonte Jackson, one of the 14 activists, told the BART board in February about the action. “I felt empowered.”

In the Bay Area, violence against black residents has taken primarily two forms, the Black Friday 14 argue. First, they say the construction of the West Oakland BART station, enabled by eminent domain in the 1960s, obliterated an historic cultural district that ran along 7th Street when it was the heart of a thriving, predominantly black community. Reverberations from that displacement and the economic hit on black residents and businesses are still being felt today, they say. A Transit Village, which includes about 2,300 new housing units, is planned near the West Oakland station. The project’s lack of affordable housing requirements concerns advocates, who say the construction will further contribute to the removal of black people from the neighborhood. West Oakland’s black population dropped from two-thirds of the total in 2000 to about half in 2010.

The second form of violence looks more like what’s been under scrutiny in Ferguson, MO, New York City and nationwide—police officers using excessive force to kill and assault black people. BART is ripe for criticism on this front, as it was BART police officer Johannes Mehserle who killed Oscar Grant, an unarmed 22-year-old, at the Fruitvale BART station in the early hours of January 1, 2009. But Grant wasn’t the first unarmed black man killed by BART police. In 1992, an officer shot and killed 19-year-old Jerrold Hall in the back of the head as he walked away, though the agency insisted at first Hall had been shot in the chest. Unlike Mehserle, who was caught on tape and served 11 months of a two-year sentence for involuntary manslaughter, the officer in the Hall shooting was cleared of all wrongdoing. In 2001, BART police shot and killed a mentally ill naked man who’d been resting on a bench at an East Bay station.

BART’s rogue policing remains a problem. Last year, officers detained 19-year-old Nubia Bowe after accusing her and her friends of dancing on the train. According to news reports and Bowe’s account, officers used unnecessary force to detain her on the subway platform before sending her to Santa Rita jail, where Bowe says she was beaten again by the jail’s guards.

That BART employs its own police force and has played a role in changing the demographics of West Oakland made it a perfect target when local activists considered how to respond to a call that business as usual be shut down nationwide November 28th, the day after Thanksgiving. Sales that day were eventually reported to be down 11 percent, a drop many who participated in Black Lives Matter actions claimed as a victory. “As long as business was still going while black lives were dying, we were going to be in revolt,” Celeste Faison, one of the 14 arrested and part of the direct action group BlackOUT Collective, told the board during a January 22nd meeting. “We’re going to keep fighting until black lives matter to you.”

Fourteen activists managed to bring to a halt a transit system that spans 104 miles and carries more than 400,000 people on an average weekday—further proof that those who have been able to shut it down, as the hashtag urges, really know what they’re doing. The action was a highly disciplined, coordinated feat that involved the 14 chaining themselves to the train while hundreds of supporters gathered around the station. It incorporated a tactic similar to those on display in other Black Lives Matter direct actions, such as those on New York City’s bridges, on the Interstate highway near Boston, or at the Mall of America near the Twin Cities, in which those involved use the positioning of their bodies to communicate a message. At that January BART board meeting, San Francisco State University professor Andreana Clay quoted civil rights movement strategist Bayard Rustin to explain why the Black Friday 14 would take such an approach: “The only weapon we have is our bodies, and we need to tuck them in places so wheels don’t turn.”

What’s odd, the protestors and their supporters say, is that other groups engaging in direct action nearby—in Silicon Valley, for instance, where a group of Stanford students shut down the San Mateo Bridge, or in Berkeley, where people shut down Interstate 80—have not been subjected to the heavy hand of the law the way the Black Friday 14 has been, with no one else who interrupted transit being asked for restitution. In the South Bay, participants in the bridge blockade are facing misdemeanor charges. Just north of Oakland in Berkeley, no charges have been filed at all, and a spokesperson for the Alameda County D.A. told a local news outlet she expects that criminal charges will be brought against “very few” of the more than 100 demonstrators arrested late last year.

One could argue, as the Black Friday 14 and their supporters have, that the Oakland group was singled out for harsh prosecution because they are black, rather than a multiracial or predominately white group, and that bringing the hammer down is a way for BART and the D.A. to dissuade other black activists from trying similarly brazen forms of protest. A representative from the group White Coats 4 Black Lives, a national organization of medical students, pointed out the disparate treatment at a February 12th board meeting: “It’s only these brilliant black organizers who have been singled out for prosecution in the Bay Area.” Later, after hours of testimony urging the board to drop the charges and restitution, BART board Vice President Tom Radulovich ceded this point after stating his support for a resolution that would have done just that. Radulovich called BART management’s treatment of the Black Friday 14 “disproportionate, unfair and unjust.”

The primary reason BART has given for asking District Attorney Nancy O’Malley not to be lenient is that BART riders were inconvenienced. The board is careful to avoid any mention of the shoppers one might first think of as the riders primarily frustrated by the action. Instead, members talk about the hourly wage workers who didn’t have the flexibility to show up late or miss work because of a travel delay. There’s a condescension in the way they reference those held up by the train that day; the implication seems to be: “You claim to be for the downtrodden, but have you really thought this through?”

Frequent exposure to effective, well-produced political theater is a hallmark of Bay Area life, so I wasn’t surprised by the ostensibly unaffiliated white people who identified themselves as BART riders and stood at the lectern to tell the train’s governing body that being inconvenienced was a small price to pay on the long road toward freedom. Marianne Maeckelbergh attended the February meeting to report that she’d been trying to get to the airport on November 28th and had already been a bit nervous about time. But when the announcement came that BART had been shut down because of political action, she’d felt a sense of pleasant surprise.

“I thought, ‘I love this city. Where am I? How is this possible?’” Maeckelbergh, a recent transplant from Holland, told the BART board, still sounding incredulous. “This is not an incident. This is an historic action.”

Perhaps through the lens of history, the fact that 14 black activists shut down the Bay Area’s subway system on one of capitalism’s high holy days will been seen as a critical moment in the early 21st century’s fight for black Americans’ dignity—just as we think of the lunch counter sit-ins, the Selma march, and the Montogomery bus boycott as touchstones of civil rights movement organizing. We’re not there yet, though, and today the 14 are nothing but trespassers in the eyes of many.

In mid-February, the BART board passed a proposal that signals a partial victory for the activists in that it drops the demand for $70,000. But the group still faces charges and will next appear in court in March 18th. “That’s fine,” Faison of BlackOUT said after a majority of board members had voted in favor of pursuing convictions. “It gives us an opportunity to put the system on trial.”

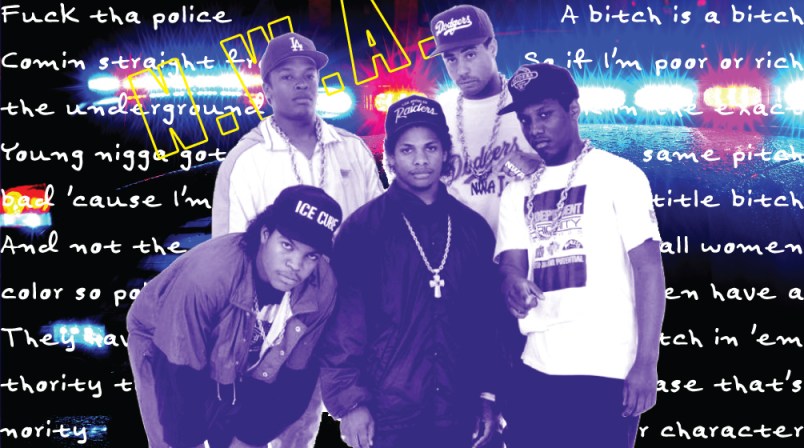

Photo illustration: Christine Frapech; Photo: AP

Dani McClain is a freelance reporter living in Oakland.

Brave people are able to end injustice. These are brave and noble people. I wish them the best.

I noticed yesterday that TPM used the language “police accountability protest” for a particular demonstration. I find that highly useful language which I might adopt for a category of present actions for which #BlackLivesMatter serves as the lead and paradigm.

I think the “brilliant tactics” the writer is so impressed by may well be the reason for the heavier official crackdown.

Shutting down a mass transit system is an order of magnitude greater disruption to a city than blocking a single road or intersection. That the action was essentially carried out by 14 people who conveniently identified themselves with chains and locks make a targeted prosecution much easier for authorities as well. The 14 are likely victims of their own “brilliance”.

Finally, the BART mass transit system serves many people for whom there is no alternative. That one woman from Holland found the disruption exciting is not an accurate indicator of the reactions of the many people who depend on BART and who don’t have alternative ways to get where they need to go.

As an environmentalist, shutting down mass transit is something I would only do as a last resort. Shutting down highways and forcing motorists to use BART is something I find easier to support.

Activists should be very conscious about the dangers of picking targets based on how easy they are to disrupt without considering the effect they may be having on the liveability of urban areas they are trying to “help”.

I assume you’re not from the Bay Area and wouldn’t know this, but shutting down the San Mateo bridge is not “blocking a single road or intersection”, it’s blocking a major traffic artery in the area, very much on par with blocking BART.

These folks are just looking for another FREE LUNCH.